Mirin

If you’ve ever made Japanese food, you may have had to pick up a bottle of mirin at the store. It’s used pretty much anywhere that a recipe calls for some sweetness in Japanese cooking, even if it is generally supplemented with sugar. And maybe you’re like me, and after having bought it once, the pantry has been stocked with it ever since.

I’ve been keenly aware for a long time that the mirin I buy at the store, even at the Asian marketplaces, is not “true” mirin, but rather a synthesized sugar syrup. You might even be able to find one with some amount of alcohol content (as it would traditionally have had), but, at least in America, that generally means it also has a high enough percentage of salt to be undrinkable on its own.

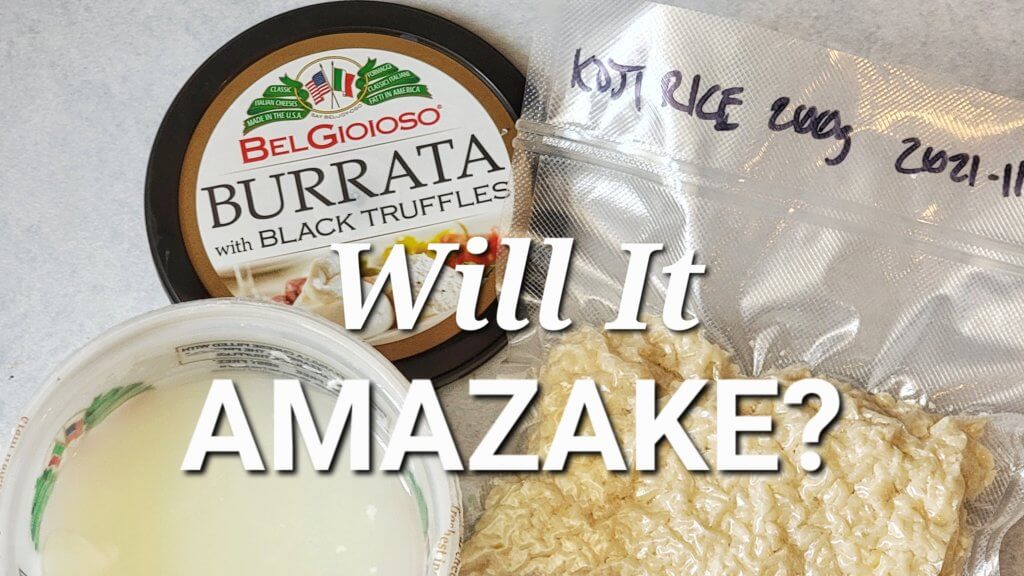

Since I started experimenting with koji, I have often wondered how mirin was made from it as a passing thought. Yes, the enzymes produced by koji break down rice starches into sugar, but the process does take some time and generally yeast and bacteria will latch on before a high enough concentration of sugar is reached to prohibit their colonization. Well, the though occured to me again today, and I finally decided to look it up. And it kind of blew my mind.

You see, the method for allowing the enzymes to do their work while also preventing microbial activity is really, really simple: just add alcohol.

When sake is produced, Koji rice and fresh cooked rice are mixed together with water. Commercial yeast is generally added to take advantage of the sugars produced to create alcohol. And whether you pitch yeast or not, naturally occurring lactobacillus will undoubtedly show up to turn that sugar into lactic acid. Once a high enough alcohol concentration is reached, the yeasts and other microbes can no longer survive.

If, instead of adding water you add an already alcoholic liquid with a high-enough ABV, you prevent the growth of yeasts and bacteria from the get-go. Therefore, to say mirin is a product of fermentation is only half correct by the strict definition. The alcoholic liquid used to protect the sugars produced is fermented, meaning that microbial activity has transformed the substance through metabolic (digestive) processes. But what makes mirin mirin is what is put into that alcohol, which is broadly a bunch of starches and enzymes. The enzymatic process, which does not technically involve living organisms, is what is responsible for the change, which we call autolysis*.

This is, of course, my understanding of the process before trying it—which I intend to do now. Also, I’ve been simply calling this “mirin”, but what we’re really talking about, and what I am going to make, is “hon-mirin”, which means “true mirin”. I know, it’s a little confusing… but apparently “mirin” is generally made with sake, while hon-mirin is made with shochu, a distilled rice alcohol.

Now, I don’t have sake on hand that I would want to use for this, nor do I have shochu, so I’ll be using what I do have: Korean soju, which at 17.5% probably falls somewhere in-between sake and shochu in ABV. Is this enough alcohol to prevent microbial activity? I have no idea! Which is why this is a logbook that you can check back in on once it’s complete in about 2 months*.

If this goes well, this could be the easiest “ferment” I’ve ever done.

There’s not much in the way of good information or recipes out on the internet. The most detailed recipe has some measurements that really don’t seem right, and they are a mix of weights and volumetric.

According to Koji Alchemy, amazake can be made with roughly 1 part koji rice, 1 part cooked starch, and 2 parts water, though I also have a write-up from one of the koji classes at Larder that uses 1 part uncooked rice. I think that generally, if I want the quickest results, I should stick to 1:1 using cooked rice. Besides, when I did cook the same weight of rice, it weighed over twice as much when done!

- 420g koji rice

- 420g cooked rice

- 840g soju

I would usually steam rice for making something like sake, and especially for growing koji, but this time I just used my rice cooker. In hindsight, steaming would have taken on less water and therefore probably have produced a sweeter, stronger mirin. I may add some additional cooked rice depending on how full the jar gets.

I added the initial 420g of cooked rice to the 2L Mason jar, and then added the soju to help cool it down. At that point it was well below 110°F so it was safe to add the koji rice and stir it up. This jar isn’t going to fit much more so that’s it until I check in on it next.

Since I measure in weight and I know the starting ABV of the soju (17.5%), I believe I can calculate the overall ABV of the mixture. I’ve essentially diluted the soju with an equal weight of rice, so that means the new stable ABV is 8.25%. That number will be thrown off when I strain off the solids at the end, but I’m more interested in the ABV at rest at this point.

I’ve used a simple non-airtight plastic lid, as I’m hoping there isn’t much in the way of gas exchange. I suppose we’ll see.

Day 6—6/11

I decided to give the jar a stir and taste. There doesn’t seem to have been any pressure build up, though these plastic lids are not even close to air-tight. Though soju is usually slightly sweet, this is definitely a little sweeter.

I got curious about the enzymes at play and the effect of the solution’s pH. This Wikipedia entry about amylase says that α-Amylase* (the main amylase enzyme that koji produces according to this Aspergillus oryzae Wikipedia entry) is most effective at a pH of 6.7–7.

Lo and behold, our mixture is right at around 7 pH. I checked the soju and it’s about the same.

Day 612—2022-02-06

I’m going to be honest with you, I forgot about this mirin. It got buried behind other ferments. It only now occurred to me that I should finish this logbook because I ran out of store-bought mirin.

I siphoned off the clarified liquid on top. I’m sorting out what to do with the heavily sedimented part which is over half of the volume—I’ll probably press it in my cider press and then let the resulting cloudy liquid settle again and do another siphon.

Just the clarified liquid alone yeilded roughly 2/3 of a liter. It filled up my store-bought mirin bottle with a little to spare. I’ll be using the extra on a pork tenderloin tonight!

I wish I did still have some store-bought “aji-mirin” to do a proper side-by-side taste test, but I can already tell this is very different. It’s darker, thinner, less cloyingly sweet, and much stronger. There is so much more umami flavor present.

I have found actual Japanese shochu near me in the year and a half+ since I started this. It also has a lower ABV (20%) than most of the suggestions I’ve found online (24%+) for making mirin with, but the even lower proof (17%) Korean soju seemed to work just fine. I have also managed to find 24% Korean soju, however, so I might use that next time.